You may think that road cycling is a genteel sport. Perhaps you picture middle-aged men in spandex cruising by serenely on expensive, immaculately maintained bikes, stopping only for an espresso and a croque monsieur at the nearest upscale café.

But cycling has a dark side, too. Bad things can happen on a bike, as I recently discovered.

It was a cool, clear Sunday morning in November. I was riding with a group of 12 cyclists, training for a long-distance race around Lake Taupo. That morning, we’d covered about 90 km already—mostly flat, apart from a steady climb through the scenic Akatarawa mountain range. I was feeling fresh and strong. What could go wrong?

Riding near Akatarawa mountain range

Quite a lot, as it happened.

To conserve energy on this long ride, I was drafting in the middle of the bunch. The road surface was mostly smooth, with the occasional bit of debris on the edges. We were going at 35–40 kph, each bike a couple of centimetres behind the one in front. That’s when things took a dark turn.

Without warning, I hit an unseen sharp rock that instantly punctured my front tyre. I yelled out, “HECK!!*”. For a crucial couple of seconds I managed to keep my bike upright, giving those behind me just enough time to avoid me if I fell.

Which is exactly what happened.

My bike suddenly flipped like a pancake and I landed square on my hip. Instead of skidding along the road and dissipating the energy of the fall, I came to an abrupt and very painful stop.

Ouch

I knew straight away that this wasn’t like bike accidents I’d had before. My breathing was out of control. I was hyperventilating, and my body was going into shock. I was half lying, half sitting on the edge of the road. I couldn’t move.

When my breathing stabilised, two of the other riders pulled me carefully away from the road and leant me against a steep grass bank. One called an ambulance, and the others waited and offered support. I could talk in short bursts. But if I tried to move, I almost blacked out with pain.

An emergency responder came from nearby Paraparaumu. He checked me for concussion and assessed my spine. I could move my toes—a good sign. Then, 20 minutes later, an ambulance arrived with a stretcher and—thank you, modern medicine!—a generous supply of painkilling fentanyl.

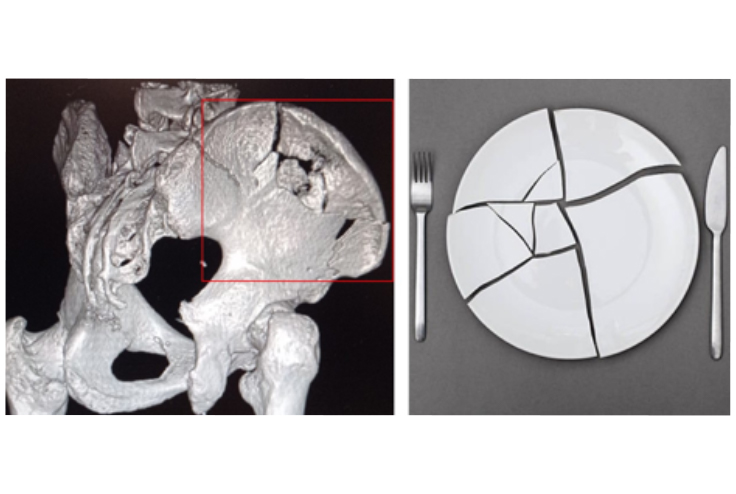

Once we got to Wellington Hospital, they took a CT scan of my hip. My right iliac wing was shattered, like a plate at a Greek wedding.

Spot the difference

The orthopaedic specialists decided not to operate, trusting that the bone would re-grow and heal by itself. I was kept under observation in the hospital for four nights before moving home.

On leaving the hospital, I was supplied with crutches, a huge, throne-like chair, a shower stool, and a special frame to place over the toilet. Now I know what it’s like to have the everyday mobility of a 95-year-old.

Recovery to road

After two months of recuperating at home, I started riding again on the smart trainer in our garage. It’s been three and a half months now, and I’m off the crutches and walking with only a slight limp. Most importantly, I’m back in the saddle for real.

This morning, I donned my new helmet and my slightly shredded gloves—a souvenir of the crash—and went for my first group ride since November.

We encountered brutal Wellington headwinds, decrepit roads, and aggressive drivers—oh, it was great to be back on the road!

*Actually, I yelled something a little ruder than that.